By Aubrey F. Burghardt

“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet…” –Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare

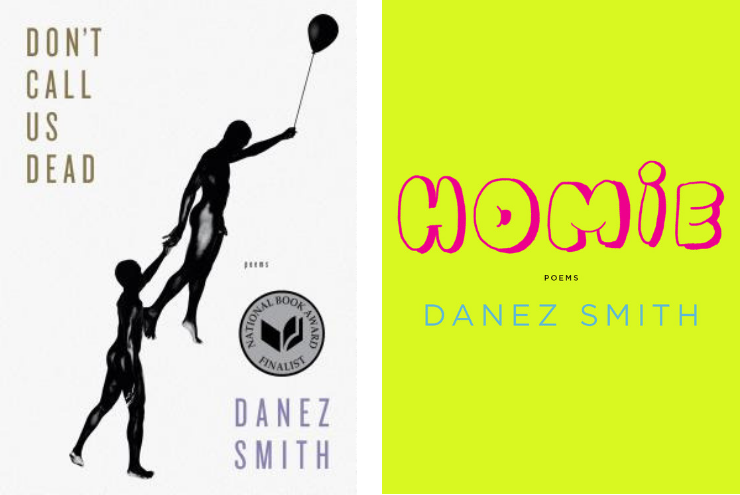

Arguably the greatest stanza ever written? Nah, I dare to say screw Shakespeare. There’s a new poet on the block. Enter Danez Smith, a Black, queer, HIV-positive poet whose works, Don’t Call Us Dead and Homie, center the true power in naming, the exploration of racism, the intimacy of queerness, and the reality of xenophobia. Smith is currently touring for the latter work, and stops in at Houston’s Brazos Bookstore on January 31.

But to honestly understand the impact of these two books, we first need to brush up on some high-school literary devices. In ninth-grade English, we learned that when classic, 17th-century, white, able-bodied, male poets reference a name that is “not a name,” that it denotes importance outside of its nomenclature. A name is supposedly a pedigree of predetermined importance, as well as a box in which things are put and labeled. To Shakespeare, a name had no worth, no value. But to Smith, a name is binding, honored, a battle cry, and something to die for. In Don’t Call Us Dead, the word “name” is mentioned over 20 times. There are 30 poems. In Homie, it’s mentioned over 15.

Homie is about homies. But also, so much more than that. It’s also about navigating language that may or may not belong to you. It’s a pivotal menagerie of poems that comes together at the intersection of Smith’s numerous identities, at the understanding of what it’s like to exist in a body defined by race, queerness, and diagnosis. It’s an ungovernable sonnet about comradery and friendship as a savior. For instance, the poem Saw a video of a gang of bees swarming a hornet who killed their bee-homie so I called to say I love you is not actually about bees. Just as references to nectar are not actually about nectar. It is about blood and alliance. It’s about homies.

Don’t Call Us Dead, the precursor to Homie, made me sob. It confused me. I got stuck on many poems I didn’t quite understand but inherently felt. And this is because Smith’s words are transcendent. They effectively communicate how hatred is felt in society, how racism affects everyone, and how love isn’t just the way someone inserts themselves into your body; but into your life and into your everyday. In this book, Smith resurrects and reburies their sadness: Black gilded youth stolen by social injustices and police brutality; a boyhood not represented in the media; a boyhood buried. There’s love, too. But Smith doesn’t differentiate between murder and loss of love. They’re the same. A name by another.

Stanzas like, “What good is a name if no one answers back,” and “whose name do you make thunder the room?,” repeatedly ask readers the question of what is in a name. And Smith answers: a name is more than a person. A name is denomination—ownership. It is shared. It is borrowed. It is given. Maybe it’s an epitaph or a cry. Maybe it’s evolving.

Homie keeps giving. There’s A note on Vaseline, a sexual, sensual, and aching physical and emotional tale on the vessel of unrequited lust. O n*gga O made me scoff in delight, the poem a Houdini of words, the E.E. Cummings of cumming. The entire work feels like a letter, one that sends a flood of nostalgia—a half-smiling memoir about the days when kids jumped off front porches because mom wasn’t home, a collective memory of youth with gestures towards Scooby Doo, Ms. Frizzle, bike rides, and Arthur, all framed to disguise the adult issues that marginalized children face head on. Their poetry is geometry, weaving in narratives of friendship, of status, and of police brutality. Smith has a way of breaking down complex statistics into remedial math.

Black.

Black and gay.

Black, and gay, and social injustice.

Black, and gay, and social injustice, mediated by Smith.

I think what other reviewers of Smith’s work have failed to mention is the impeccable scale of their visual poetry. Smith doesn’t distract with their words; they instead offer a map to experience each line. Reading Smith’s works reminded me of one of the most lauded visual poets in history, E.E. Cummings. There’s a similarity in the geometry. It’s there in the strikethroughs, in the overlapping of words, in the linguistic repetition. Smith’s words are a declaration: their words are theirs, but they’re also ours, and our words are also theirs.

Danez Smith will be in Houston at Brazos Bookstore on Friday, January 31, 2020. You can buy your book in advance to be signed at the event. For more information on Smith’s poetry, visit danezsmithpoet.com.